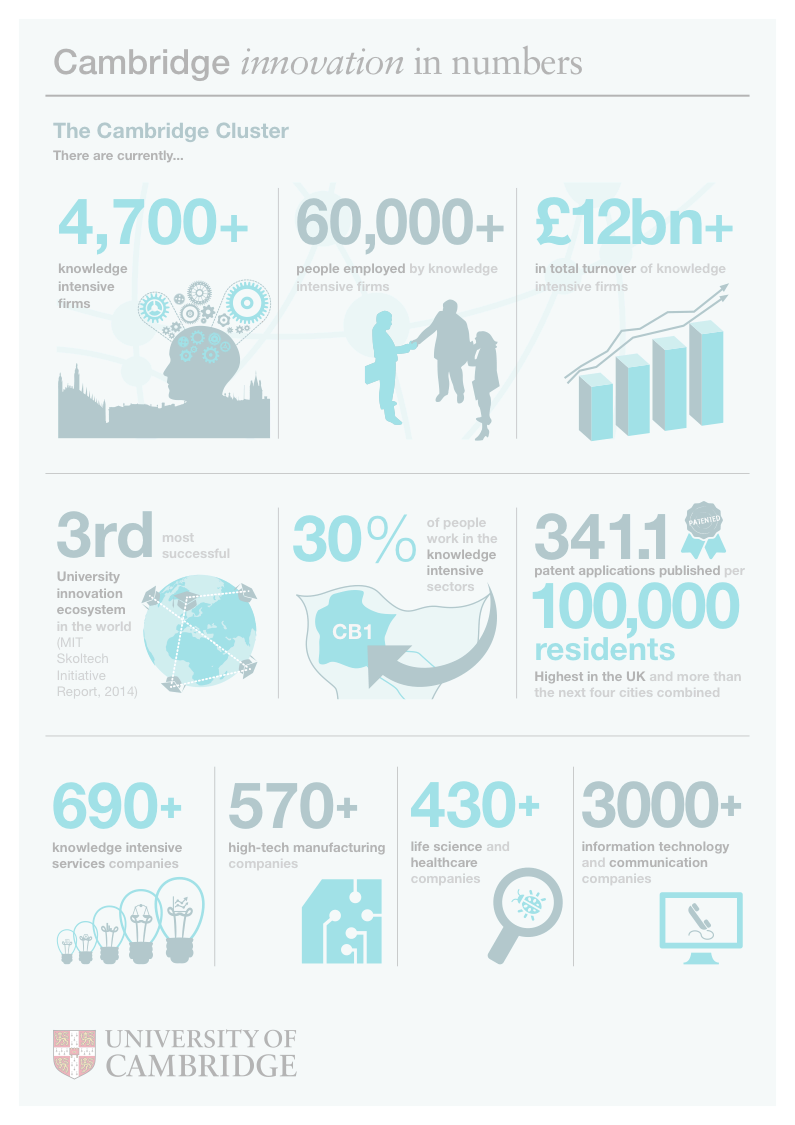

Cambridge University has a very prestigious reputation worldwide. It can boast it employs a total of 96 (!) Nobel Prize winners. And it has also achieved remarkable successes in the field of commercialization of science. This world renowned university has established an independent and highly successful company for technology transfer. I had the opportunity to take a look into their “kitchen”. Now I would like to share a few insights with you, which could offer a great inspiration to the domestic academic sphere.

Cambridge Enterprise – The Success Factory

The distinguished Cambridge institute has unified all its activities relating to the commercialization of university research under Cambridge Enterprise – a company owned exclusive by the university. The main goal of Cambridge Enterprise is to convince faculties that the commercialization of research is not in conflict with furthering the knowledge and academic freedom, but on the contrary.

Over the past thirty years, this company has been ensuring that the majority of knowledge and inventions from the university finds actual and purposeful use. This year Cambridge Enterprise decided to share its knowledge and know-how with experts from other countries in order to use international research and benefit the whole of society.

Its one-week open programme was attended by fifteen representatives from around the world, including myself. It focused on very interesting and exceptionally topical themes. In addition the Cambridge model success, the programme also focused on transforming an idea into a good business model, and how to proceed with idea licensing or obtaining finances. Another important topic was discussing when it is better to cooperate on the basis of a licence and when it is better to establish your own company. Simply put: how to get research from the laboratory to the people most effectively, and in a manner that will benefit the scientists, university, investors and the entire society.

No one gets beaten

Setting the right expectations on the part of researchers, university and also investors, is the key for successful transfer and commercialisation of research at Cambridge. The yields from successful transactions can be immense. However, the sale of a university firm together with the team can easily take as long as ten years. It is thus clear that if such demanding process fails it generates enormous frustration on all sides.

Cambridge Enterprise is thus very keen on ensuring that none of the three parties is harmed in the process. Unfortunately, in the Czech Republic we often see that this is not the case.

In the Czech Republic universities automatically acquire know-how. However, if the university and the researcher do not agree on cooperation, the researcher takes the know-who, which he or she does not own, elsewhere. Usually to his own company for which he acquires investors. And the university is left empty-handed – it has nothing from the research that originated on its soil, using its resources.

For example, at Cambridge Enterprise it is common to do an “idea validation. This helps to ensure that the investor does not receive something that has no chance on success. It is obvious that in such a scenario the university would lose the investor, most likely forever – something Cambridge University, continuously ranked among top five universities in the world, cannot allow to happen.

When introducing an idea to commercial sphere, it is important to be certain of its qualities and not to waste time, energy and money on unnecessary things. The university takes maximum care to reduce the risk of failure. That is why it first of all thoroughly examines the market situation by seeking answers to fundamental questions, which include the following:

- If we transform this idea into a service, product or process, will anybody buy it?

- How much are the end users / investors prepared to pay for it?

- How big is the attainable market?

- How can we access this market and how much will it cost?

- Shouldn’t we be spending our time on something else? Something that has greater potential?

The university obtains answers to these questions using various market researches and analyses, which it either conducts internally or in cooperation with designer studios and innovation labs such as Direct People.

The university must offer services that Scientists actually want

A big surprise to me was the intellectual property policy. Masters and postgraduate students automatically own the rights to their discoveries. And employees, i.e. researchers, are the ones who decide whether they want to commercialize their work.

The university only gets the rights once the researcher chooses to register its intellectual property together with it. However, he/she can also choose to cooperate with an investor or use other resources. Thanks to this liberal policy, Cambridge drew the attention of many top international scientists.

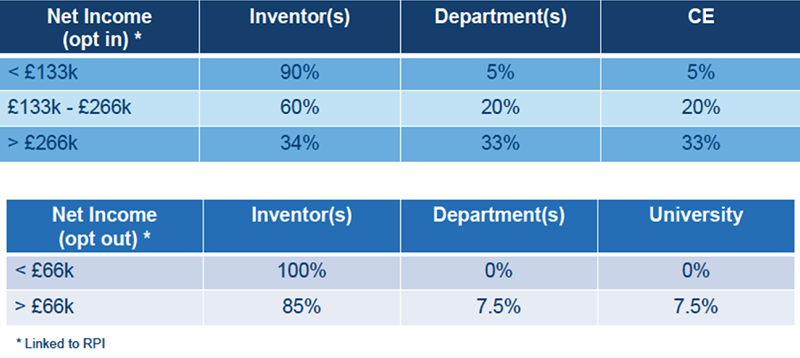

Income distribution

OPT-IN: Cases in which the researcher (inventor) decides to protect his or her intellectual property together with the university.

OPT-OUT: Covers cases of cooperation with an investor.

Among other factors, the fact that the university does not automatically own the idea has a very positive impact on its approach to researchers. Cambridge Enterprise must do its best convince researchers to use its services, so that the university itself can also profit from the commercialization of the idea.

For example, within the framework of the research cluster, the university operates the Centre for Corporate Research, that is used for by firms like Microsoft, Toshiba or Unilever. It incorporates 19 science and business parks, six incubators and accelerators, a number of “angel investors”, venture capital funds and commercial networks, and arranges a range of activities in support of enterprise. Cambridge Enterprise also offers the possibility of contractual research, protection and management of intellectual property, investment fund services etc. And in this it has no problem to maintaining its competitive edge.

What to do with a promising technology? Found a company? Sell a licence? Or…?

For the successful technology transfer from the university, it is essential to choose a correct form of sale of research activity and its outputs. And this is far from simple.

Naturally, various models exist for monetising research. For the purpose of explanation I shall present a simple example of a researcher who invented a relatively simple procedure of diagnosing “microRNA”. This method may represent a significant tool in the battle against cancer, and could bring a genuine revolution in this field. What possibilities are available? One is to start building a firm. However, this means competition for a whole range of other firms that have already existed for decades, and logically have a head start on a newly founded company.

Another possibility is to sell the idea like a “cookbook” (of expertise), perhaps “together with the chef”. In other words: it is possible to sell a licence. This is mostly utilised by commercial firms and the researcher then receives payments by means of license fees. This may be in the form of fixed reward, percentage of sales or percentage of the profit.

I was intrigued that the “rainforest” approach to research is used at Cambridge. This means the ideas “grow” organically and spontaneously. Whereas in London, where they are even more successful in the field of technology transfer, priority is given to the “plantation” approach. The plantation approach determines, which ideas to “cultivate” and actively support their growth using design thinking and “service designers” meaning companies like IDEO in the international field, or Direct People in the Czech Republic.

Scientist as businessman is a trend – let’s follow it

All technology transfer centres worldwide suffer from a shortage of quality people. While almost 60 people work at Cambridge Enterprise, at the University of Vienna the work is covered by only two employees. And we could find hundreds of such examples.

It is interesting that employees at Cambridge Enterprise – unlike the majority of other centres – are neither exclusively traders nor exclusively researchers. Most of them have both a doctorate and very good commercial skills and experience. MBA is no exception.

Scientists – not only in the Czech Republic – are often engaged in scientific activity, but only handful of them can also do business. Scientists around the world are gradually learning to do so but our university still environment is among the weakest.

During the open programme at Cambridge University I also found out there are many similarities with the Czech Republic. It shows that we have come a long way and have a lot to be proud of. However, if we wish to join the big league in the field of technology transfer, then we still have a long way to go.